Note: The first half of what follows is a revised version of, Is the left–right spectrum in flatland? A better way to graph Ron Paul (13 January 2012). It is followed by a new critique of the personal/economic dichotomy and the Nolan Chart, which is built on it. Minor copy revisions were made on 24 January 2014.

The Ron Paul campaigns badly strained the interpretive power of the conventional left–right political spectrum. The San Francisco Chronicle took a stab at placing Paul somewhere along it (Is Ron Paul left of Obama, or a throwback to Ike?). Even the Paul campaign itself at times engaged in nomination-trail rhetoric to establish which candidate was “more conservative,” which is generally understood to mean more to “the right.” This tactic may help win some votes, but is it accurate?

What if we could graph the core positions of the Paul campaign without trying to squeeze them into the usual left–right spectrum? What if that spectrum itself is analogous to the imagined world in the 1884 novel Flatland? In Flatland, two-dimensional beings live as flat geometric shapes within a plane. One day, residents are shocked by a three-dimensional being who, while passing through their plane, seems to appear out of thin air, change shape, and then vanish again without a trace.

Back in our world, how might we locate an entire additional dimension of political spectrum? It is made to seem as though the whole range of possible opinion must exist somewhere along one line. Such a line is only one-dimensional; it does not even allow us the Flatlanders’ relatively generous two.

What if we add a second dimension? Imagine looking down at two lines that form a cross on the ground. The usual political scale stretches out to your left and your right, but a second scale crosses over that one. The “front” is closer to you (a living human person, as it so happens) and the “back” is farthest away from you (in the realm of abstractions that are supposed to trump the value of real human persons, as it so happens).

Now what if the whole left–right scale could have some thickness, making it more of a band rather than a line. This whole band could then be seen to move along the front–back scale over time. This could be used to represent a gradual movement of a whole political culture, even as the relative positions of left and right to each other remained. I will label this new scale with subjective percentages to illustrate relative positions and directions of movement over time. The precise numbers will not be as important as the relative positions they indicate, yet it may be clearest to begin from the farthest extremes as ideal types.

Far-out definitions

Let us say that all the way at 100% in the back of this new scale is totalitarianism. This is the idea that the state can and should do to and with individual people and variously defined groups whatever it pleases. The historical “far right” fascists and “far left” communists had different flavors of totalitarianism in common. Adherents to such views thought that their own favorite party should rule over any individual or traditional civic or community interest. In this sense, the familiar litany of 20th-century dictatorial leaders such as Stalin, Hitler, and Mao, stood side-by-side on the front–back scale. This is not to ignore their many differences; it is only to say that when viewed along this scale, their differences were incidental and their commonalities overwhelming.

Now let us say that all the way in the front of this new scale at 0% is philosophical anarchism. This is the idea that the state has no justifiable place within human societies at all. This body of thought also comes in a range of distinctive “left” and “right” versions with regard to the ideal rules and institutions for a statefree society, such as mutualist and private-law models. Fewer people are familiar with such distinctions, but here is a breif hint at the range of viewpoints possible here. Toward the left, mutualists emphasize such institutions as cooperatives, labor-unit trading associations, and an occupancy theory of land ownership (the illegitimacy of absentee ownership). At the other end, “private law” philosophies refer not to each person having a law unto themselves, but to the quite opposite idea of upholding legal principles that are equally applicable to all people in their capacity as “private” persons, allowing no special exceptions to general rules for “public” agents, such as those special exceptions to general rules that are made under “public law.”

This raises a puzzle for the usual left–right spectrum. It is able to combine left totalitarians and left anarchists at one end and right totalitarians and right anarchists at the other, a major case of lumping together quite opposite views. Imagine Stalin and a peasant freely trading units of labor time. Sounds dodgy. Imagine national socialists promoting a set of universal social norms that apply equally to all human beings everywhere regardless of grouping and classification. Sounds even more unlikely. Something about this scale, taken alone, therefore seems far too simplistic. A naive observer of the left–right scale alone might be forgiven for assuming that the two sets of “opposite” anarchists and “opposite” totalitarians, while they might disagree on many issues, might be at least as likely to find common ground with one another as with their alleged neighbors.

This raises a puzzle for the usual left–right spectrum. It is able to combine left totalitarians and left anarchists at one end and right totalitarians and right anarchists at the other, a major case of lumping together quite opposite views. Imagine Stalin and a peasant freely trading units of labor time. Sounds dodgy. Imagine national socialists promoting a set of universal social norms that apply equally to all human beings everywhere regardless of grouping and classification. Sounds even more unlikely. Something about this scale, taken alone, therefore seems far too simplistic. A naive observer of the left–right scale alone might be forgiven for assuming that the two sets of “opposite” anarchists and “opposite” totalitarians, while they might disagree on many issues, might be at least as likely to find common ground with one another as with their alleged neighbors.

Some readers may by now have thought of the well-known “Nolan Chart,” which may at first seem similar to the model proposed here. However, the Nolan Chart is actually different in important ways, the implications of which we will explore below.

An example: Applying the front–back scale to American history

Where might 1770s American revolutionaries appear on the front–back scale? Some were probably around 0–10%, depending on which ones. They were rebelling against perceived overreaches of monarchy and mercantilism and wanted to replace them with somewhere between nothing and as little as possible, that is, with a novel “limited” state that was supposed to differ substantially from monarchism.

As usual, there was a division between the “left” and the “right,” in this case between the revolutionaries and the loyalists. This difference was largely over the question of what the proper natural order of society was. What represented the true natural order of society? Was it familiar monarchy or some novel form of self-government? It can be hard for us to imagine today that at that time, it was monarchy that appeared to be the self-evident natural order and self-government the seemed to be a reckless new social experiment.

Both revolutionaries and loyalists generally viewed society as a kind of natural order, a few that is closer to the front of our proposed new scale. This contrasts with central planners deciding how society should be, and then using the police powers of a state to engineer it that way, closer to the totalitarian end of this scale.

After the revolution, some, particularly the Hamiltonian Federalists, were still in favor of a powerful state, just one that they would run instead of some distant monarch. Few today, even in the Ron Paul camp, seem to recall that many Jeffersonians already viewed the Constitution of 1787 as a dangerous step toward perpetually growing government, one that clashed with the revolutionary ideals of 1776 and had already most likely been a net victory for big-government Hamiltonians. As it has turned out, the entire American political culture has been moving toward greater state power since soon after the revolution, and judging from the impressive scale of the current US Federal government, which that constitution set up, the anti-Federalist Jeffersonians were correct.

US history using the left/right scale can be viewed as having progressed in a zig-zagging pattern between “left” and “right,” represented by various parties in different epochs. However, this simple, one-dimensional story tends to obscure a pervasive undercurrent in which left, right, and center all move “back” together along a second dimension—in the direction of a more powerful central state in all areas.

It has often been observed that the modern US Federal government’s effective powers vastly exceed those that most monarchs would have dared even imagine. Modern powers to tax, borrow, and inflate are immense and business and life are hyper-regulated. In other words, the entire left–right scale, as a band, has been moving along the front–back scale toward the back for a long time.

Where is this band now? Centered around 65%? More? Each observer might suggest a different subjective number, but it has moved far from its former positions and the “consensus” direction of movement remains toward more central state power.

Where on this front–back scale should one place “legalized” extralegal military detention or assassination? What about raids on small-scale farmers selling to eager customers in search of more healthful products? What about detention without charge based on the failure of snoops to understand modern English idiom in the tweets they scan?

The original French “left–right” model was focused on the question of change. Should the familiar old ways be preserved or should something new be done? Included in the “left” were the great French economists Bastiat and de Molinari, who wanted to largely or completely eliminate the powers of the state to let civil society and economy function properly. They did not want to transfer those same or greater powers to some other form of coercive organization. Their main goal was to eliminate those powers, not reassign them. Left-wing “change” originally meant reducing the powers of the state and the cronyocracy.

A preference for change versus a preference for the status quo is a highly contextual distinction. Change what? How? In what direction? The original left–right concept itself is relational; it emerged in a particular historical context. In today’s context, however, the model applies quite differently. In fact, the presumed direction of desirable “change” now seems to mean exactly the opposite of what it once did.

Things are not better at the “right” end. The idea that the modern right wants smaller government is a faint ghost from the “Old Right,” whose ideas survive in mainstream politics as mere words devoid of effective content. The modern right generally wants the central government to be bigger and stronger in somewhat different places than the modern left does. However, both major parties have long been united in the big picture on ratcheting up government; they just differ at times on exactly how, where, and for the benefit of which blend of special interests.

From the perspective of any quite different position along the front–back scale, the major parties have become increasingly indistinguishable in practice on the most important issues, issues such as war versus peace, police-state versus republic, and technocratic central planning and cronyocracy versus authentic economic liberty.

How to graph Ron Paul

Whatever one’s opinion of Ron Paul, it is widely agreed that he is focused on making serious changes to status quo policies. Relative to him, then, all of the other candidates, the sitting president included, are broadly in favor of the status quo. Moreover, the “status quo” itself is not static; it is a moving pattern of massive state growth. Most of the talk of “cuts” in Washington refers to reductions in the rate of growth. Thus, Paul, who is from the “right” according to conventional wisdom, is far “left” on a “change versus status quo” scale applied to today’s context. The change he wants, however, is in the opposite direction from the one usually presumed – away from centralized state interference in people’s lives. Graphing that requires another dimension.

By stepping back from the permutations of the left–right scale, we can more clearly view Ron Paul’s 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns as appealing to issues better defined along the front–back scale. Paul himself opened his 2008 The Revolution: A Manifesto by deconstructing the false alternatives the modern left–right scale sets up. In contrast, his unique location among modern politicians on our proposed front–back scale better explains his broad crossover appeal on certain key issues.

Imagine the whole left–right scale nowadays as a band crossing over the front–back scale at somewhere around 65% central state power. The real Ron Paul would be effectively invisible to anyone looking only along the usual scale from left to right. Conversely, he might stand out in the eyes of others for exactly the same reason. He is the only candidate who is substantially off of the left–right band as it is currently positioned along the front–back scale. He therefore appears either 1) completely unfathomable, as the three-dimensional character was to the two-dimensional Flatlanders, or 2) as the only intriguing alternative to the various flat shapes within our usual political flatland.

Mainstream candidates of both parties argue about how and where to grow state power. Meanwhile, Ron Paul is saying that we should be moving that whole state power meter, left, right, and center, in the other direction along the front–back axis.

There are always left and right camps on each major issue and in each historical context. One side might lean more or less toward the front or back, tilting the angle of the whole crossing band one way or the other. Nevertheless, a monocular focus on the left–right scale obscures the long-term movement of the entire political culture toward greater central state power and away from individual liberty and civil society institutions.

We are supposed to be enchanted by the theater of differences between the heads of a two-headed beast. We are not supposed to notice that the whole two-headed beast has been lumbering in the direction of ever-expanding powers for itself and special privileges for its camp followers of all parties. That makes it encouraging that more and more people, especially among the young, are beginning to notice. Could this be a sign that the illusion-holding power of the one-dimensional left–right scale is weakening?

The three-dimensional visitor to two-dimensional Flatland was not a beast, but the two-headed bipartisan leviathan is. Ron Paul is the only candidate who is working to turn that whole beast around and walk it back toward its cage.

The personal/political dichotomy and the Nolan Chart

We have examined the implications of adding a new dimension to the political spectrum, one that crosses the left–right spectrum and runs from front to back between the political ideal types of philosophical anarchism and totalitarianism.

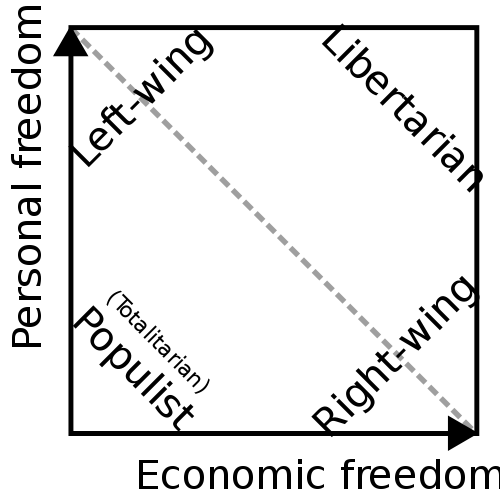

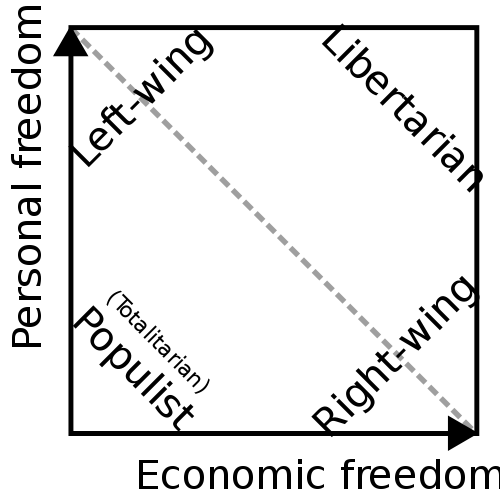

The Nolan Chart was also an effort to add dimensionality to political interpretation to help people question and see beyond the left–right spectrum. David Nolan developed it in the early 1970s and it forms the basis of the well-known “World’s Smallest Political Quiz.”[i] The Nolan Chart divides the world into “personal” and “economic” realms to illustrate a seemingly paradoxical preference of the left for more freedom in “personal” areas and less in “economic” ones, with the inverse set of preferences on the right, which allegedly prefers economic freedom and enforced social control. Libertarians are depicted in another corner preferring freedom in both personal and economic areas, while totalitarians (or communitarians in one variation) are placed in the opposite corner, insisting that some other set of political considerations should take precedence over liberties.

The Nolan Chart was a substantial improvement over left–right reductionism. It allowed space for possibilities that are invisible along the left–right spectrum, namely libertarianism. Simply conflating libertarianism with “the right” is deeply confused and tends to lend an undeserved laissez-faire credibility to the fundamentally authoritarian right. This perspective also suggests that the main risk of the Ron Paul movement attempting to work within the Republican Party is that, as is often the case, vote-catching words can be assimilated into the conventional party while their meanings are ignored.

The concept of a scale that runs from total state control to no state control at first appears the same as in our proposed model. The important difference is that the Nolan Chart uses two distinct scales of freedom, each one qualified. This turns out to be an important difference that reveals some of the Nolan Chart’s weaknesses and shows how a still deeper layer of illusion is embedded in the conventional left–right spectrum.

Source: Wikipedia CommonUses and possible origins of the personal/economic dichotomy

Source: Wikipedia CommonUses and possible origins of the personal/economic dichotomy

The Nolan Chart’s most important weakness is that it accepts the conventional division of the world into personal and economic realms. This may seem uncontroversial at first, but as we examine this division step by step, and from various angles, the separation between personal and economic realms, used as a political assessment tool, may begin to look more and more flimsy, to the point that it may seem to fall apart altogether.

First of all, it may be that separating personal and economic categories is in part a legacy of certain economists’ attempts to create an artificial, reductionist model of “economic man.” Such a creature fit into mathematical and deterministic models much better than pesky living people. An “economic” calculating machine devoid of “personal” idiosyncrasies was just what advocates of such models needed if they were to make them seem relevant.

In contrast, Ludwig von Mises argued that real economics:

…deals with the real actions of real men. Its theorems refer neither to ideal nor to perfect men, neither to the phantom of a fabulous economic man (homo oeconomicus) nor to the statistical notion of an average man (homme moyen). Man with all his weaknesses and limitations, every man as he lives and acts, is the subject matter of catallactics. Every human action is a theme of praxeology (Mises [1949] 646–47).

A second perspective is that the personal/economic dichotomy may have arisen out of differing streams of rhetoric used by advocates of political control over people. Different threads of coercion-justifying rhetoric have different historical and philosophical origins, some of which are more “economic” and some more “personal.”

Listing up the various elements of life into categories is itself an artifact of a bureaucratic view of life. It results from habits of “seeing like a state,” in the memorable phrase of Yale Professor of Agrarian Studies James C. Scott. State administrators are eager to divide out and prioritize attention on those parts of the real world that are “legible and hence appropriable by the state” (Scott 2009, 39). Thus, what the state and statists view as “economic” will tend to involve those aspects of social life that are easiest for the state to regiment, monitor, and measure from the outside and, most importantly, tax. The production of grain was historically a worldwide favorite of states in this regard. From field to storage, it is visible, trackable, measureable, divisible, and therefore most readily taxable.

On the other hand, interest in using the state for social control of the “personal” realm may be associated more with the mashing up of law and religion. For example, in considering the impact of the 16th century German Reformation on the Western legal tradition, the late Harvard legal scholar Harold J. Berman argued that, “What has traditionally been called a process of secularization of the spiritual law of the church must thus also be viewed as a process of spiritualization of the secular law of the state” (2003, 64). Secular law was increasingly infused with the quasi-religious objective of attempting to make people “better” by using police powers to force them to perform certain lists of duties that religious bureaucrats defined as “moral.” This basic approach of attempting to use the state’s coercive powers to press-gang others into joining in a pursuit of moralized objectives may be traced right up to the assumptions underpinning a host of forcible modern wealth-transfer bureaucracies.

This latter, more “personal,” coercive dynamic today coexists with the more general interest of states in categorizing and directing “economic” activity into those channels that can most easily be recognized, measured, and exploited. Nevertheless, control and freedom are not so easily separated, not in theory or in practice, especially when viewed over the longer term.

Is that personal or economic?

But surely, you might say, we can set aside such theoretical considerations and try to list some categories for “personal” versus “economic” areas of life that everyone can agree on.

Very well. We might start with some typical subjects of political discourse: employment, education, housing, religion, marriage, and food. Consider each one in turn.

Is it clear which area is personal and which economic? Perhaps this should be examined more closely.

With greater “economic” independence of decision-making, a given person may enjoy greater freedom of “personal” action. So is such freedom definable as economic or as personal?

One might imagine a guaranteed “personal freedom” under some constitution or another. Does one still have such freedom when it no longer extends to whatever that particular state has most recently decided to reclassify as an “economic” area of life? Surely your “freedom of expression” on the Internet is subject to certain “economic” regulations of the medium or the “economic” products and services you use to access it, is it not?

Or it may be that your “personal” freedom from yesterday is actually covered by “interstate commerce” today. Or maybe it has some bearing on “national security.” Either way, the practical message may well be, “Sorry folks, that was yesterday’s freedom. This is today.”

What about one’s ability to open, relocate, expand, or contract one’s own business? What about one’s choice of place of work and of co-workers, one’s place or type of residence, what foods one can or cannot eat or sell, or where, how, and when oneself or one’s children are educated?

Those are all “economic” matters in some ways. But are they not also each very personal? Clearly, they impact large portions of the days and hours of one’s life and the quality and content of one’s experiences. They can also all impact issues of employment, saving, retirement, income, and expense, which of course makes them all…What? impersonal?

But surely we can all agree that marriage is completely personal! Well, marriage within modern states is in effect a bureaucratically defined legal status that has a direct bearing on tax rates, exemptions, and insurance coverage. It surely has major impacts on the financial affairs of all those involved, impacting bank accounts, housing, transportation, inheritance, the distributions of child-rearing expenses, etc. So then marriage is actually “economic” rather than “personal”?

Will the seemingly solid personal/economic division really go down that easily? Maybe we should give it one more chance. Surely we can define it objectively for all people this way: the “economic” has something to do with the use of money. The economic is the monetary.

All right, then, let us try this one out. What are some quintessentially “personal” areas within conventional political discourse? How about vice? This is one of those personal areas that the right is famous for wanting to use the police state to control, including areas such as prostitution and substance use.

People acting within such realms almost invariably employ, well…money, for transactions. One might suppose that actors in these sectors also use money for at least some degree of budgeting and cost accounting. So the money = “economic” attempt at a definition soon begins to break down once again.

Out of the paradox

One secret to unraveling this puzzle is that both the personal and economic categories themselves are subjectively defined. They make the most sense when viewed from the perspective of a person considering his own decisions in a given context. They depend for their meaning and application on how each issue is being viewed, who is looking, and why the viewer is asking. The question of whether an issue is personal or economic is itself an individual matter. Who wants to know?

For example, if Anna decides to take a particular job, she might think to herself that she is mainly doing it to advance her career in an interesting work environment, which would make her decision lean more toward the “personal” side of things. However, she might also decide to take the same job mainly for its income potential, which might make her think of her decision as more of an “economic” one. From a rigorous economic-theory perspective, observers cannot determine this distinction from the outside one way or another, as it has to do with how the acting person is conceptualizing what they are doing in terms of ends and means.

It would also not suffice to ask the regional economics czar or the head of the Bureau of Personal Satisfaction assigned to the territory in which Anna lives. In any case, those two bureaucracies would not be likely to agree even with one another. After all, the classification of her action might impact their respective budget appeals next year in different directions. As for Anna’s decision, only she can really know what her decision was mainly about. She might never even tell us the truth about why she took the job, depriving us of any chance to effectively use our neat little bureaucratic categorization scheme into “personal” and “economic” statistics.

The personal/economic distinction referenced in the Nolan Chart and other political charting models, while at first seeming intuitive and clear, thus turns out to look increasingly arbitrary and malleable the more closely we examine it. Moreover, the distinction depends on categories that help define the same conventional left–right spectrum that we have been attempting to build a pathway for transcending.

Indivisible

To the extent that the personal/economic distinction might be meaningful at all, it is also important to recognize that when the state controls either alleged “half” of freedom, it already has the leverage to control the other half. Those who use or threaten state-orchestrated violence to control others in the “economic” realm also gain discretion over them in the “personal” realm, and vice versa. This is not to say that authorities with discretion to direct violence to control the lives of others will actually do so in any particular way at any given time. Each state, for example, remains somewhat different from the others in its current style and practices. The key is that they can.

The personal/economic distinction functions within statist discourse to help sell state control, but different packages are available to appeal to different sets of preferences. The “left” version says that you can have your freedom in the personal realm so long as the state has the discretion to tell you (mainly tell other people, of course) what to do in the economic realm. The “right” version is the mirror image. You can have your freedom in the economic realm so long as the state has the discretion to tell you (mainly tell other people, of course) what to do in the personal realm.

Each seductive package appears to make sense right up until the moment it is too late. That is the moment when the creature you have been supporting tells you what to do in an area over which you had preferred to retain personal control. The secret power of this distinction is its “confuse and exploit” effectiveness against entire populations of individuals, each of whom is willing to buy into some attractive, customized variant of this deceptive pact with the devil, and pay for it—with other people’s liberty.

All of these packages, however, are long-term scams, or “long cons.” Neither variant of half-freedom is meaningful if you cannot act in disagreement with the authorities who control “the other half.” Whichever half of liberty has been ceded is held in reserve and can always be used to undermine the half that supposedly remains. The key is that with any such scheme of divided liberty, you are left with no reliable foundation from which to disagree—and act on such disagreement—without facing the threat of officially meted-out fines, confiscation, imprisonment, or death.

Citizen A, for example, might be arrested and imprisoned for a “personal offense” such as sampling some forbidden substance. While in prison, she will not be able to exercise her “economic” freedom by continuing to work at the company she started. Meanwhile, Citizen B’s “economic offense” of creating a popular website that offends powerful incumbent economic interests with strong lobbying operations might likewise land him in the lock-up, from which his “personal” life will be out of reach.

Say you want to start a food co-op with your neighboring farmers and friends. This is an exercise of “economic” action in support of “personal” food freedom. However, this risks running afoul of the government’s bipartisan system of food regulation and its lobbyist-driven support for certain kinds of politically favored industrial products that are marketed for human consumption. Having been duly raided and warned, you would probably be arrested if you persisted too far. Before long, both your “personal” and “economic” freedoms might be narrowed down to the choice of eating the agro-congressional complex’s mystery-grain GMO prison chow or going on hunger strike.

Differently labeled frogs in the same pot

The overall preference for state control over civil and individual freedom in all areas has been rising – left, right, and center. Meanwhile, all the little frogs divided into their left, right, and center teams, are focused on their differences along the left–right spectrum. What none of them seems to notice as they croak back and forth is that the water temperature in the pot they are all floating in together is rising.

The image of the entire left–right spectrum as a band shifting along the front–back axis over time makes even more sense if the division of the world into “personal” and “economic” realms is illusory. All freedoms, or their absence, are ultimately interdependent and, in the big picture, tend to rise and fall together.

The fake division of the world into personal and economic realms has proven an effective mechanism for helping to divide and control every one of those hapless simmering frogs. Even the venerable Nolan Chart, while it went a long way toward expanding political perspectives, did not manage to fully transcend that division. Taking a fresh look at the Ron Paul movement in these terms may help us all enhance the dimensionality of individual acts of political interpretation.

References

Berman, Harold J. 2003. Law and Revolution II: The Impact of the Protestant Reformations on the Western Legal Tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mises, Ludwig von. 1998 [1949]. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. The Scholar’s Edition. Auburn, Alabama: Mises Institute.

Scott, James C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[i] There have been many alternative charting attempts over the years since the Nolan Chart. I recently discovered that the Political Compass Organization had already proposed a two-axis model with even more visual similarity to the one discussed here. Looking further, however, it seems that that chart’s labeling and the underlying assumptions suggested in its diagnostic test still end up differing considerably from the model I suggest. I base this quick assessment on the chart’s labeling, the actual questions on the accompanying test, and the somewhat surprising result I obtained from taking it (hardly where I would have placed my views on it by looking at the definitions).