Another bump on the road: Bitcoin and bubbles revisited

/ Japanese “bumpy road” sign for MtGox. 路面凹凸ありOverload, delays, and the temporary closure of the MtGox exchange seem to have been proximate triggers for a sharp Bitcoin correction on April 10–12 from dizzy highs.

Japanese “bumpy road” sign for MtGox. 路面凹凸ありOverload, delays, and the temporary closure of the MtGox exchange seem to have been proximate triggers for a sharp Bitcoin correction on April 10–12 from dizzy highs.

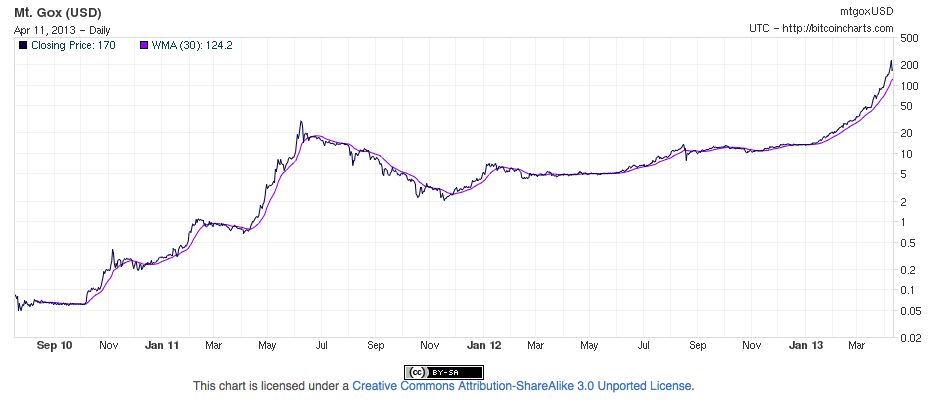

As trading graphs fell freely, some Bitcoin critics appeared gleeful to believe that their prophecies of the Bitcoin phenomenon being nothing more than a delusional bubble might be coming true. Commenters promptly took to the internet to gloat at the short-term losses of naïve traders and bask in their own contrasting wisdom.

In this new context of short-term sentiment, it may be useful to revisit and refine my recent critique of the dismissal of Bitcoin as being nothing more than a bubble or even a sort of Ponzi scheme. In Hyper-monetization: Questioning the “Bitcoin bubble” bubble (6 April 2013), I offered an alternative to the popular interpretation of the long-term rise of Bitcoin’s exchange value relative to fiat money. This was especially intended to address the view that Bitcoin is nothing more than a bubble. The most insistent proponents of this view elaborate along these lines: “Bitcoin has no ‘intrinsic value’ and is therefore ultimately destined to fall to its ‘inherent’ value, which is zero, completely wiping out any true believers still left around for its inevitable and welcome extinction from the universe.” Or something like that.

“Is” versus “in”

A more subtle approach to calling a “Bitcoin bubble” is also available, and has long been advanced by several people with more nuanced understandings of the system. First, Gavin Andresen, lead developer of the open-source Bitcoin Project, wrote nearly three years ago in a short post Bubble and crashes (9 July 2010) that he expected multiple recurring bubbles over the course of several years.

Bitcoin will get mentioned someplace with lots of readers, a bunch of those readers will like the idea and try to buy Bitcoins, their price will rise, which will draw even more people to “invest”, which will drive the price up even more…until people decide that the price isn’t going to rise any more and everybody rushes to sell before the price drops. I predict there will be between one and five Bitcoin bubbles (price will double or more and then crash back down below the starting price) in the next four years…I think it will be impossible to tell if a bubble & crash is “natural” or “the men in black helicopters” manipulating the system.

Second, Rick Falkvinge, who had also called a short-term bubble and a correction to $60–$65, has long identified currency exchange services as a weak link in the wider Bitcoin “ecosystem.” See his 12 April post What we learn from this Bitcoin correction. A commenter on that post wrote, “I would not call an 80% move a correction…” to which Falkvinge replied, “It is not the downslope that is abnormal, it is the upslope. A value that reverts to where it was two weeks ago is normally a mild correction.”

Finally, Peter Šurda who steadily focuses on the importance of liquidity, infrastructure development, and scaling over price, re-summarized in a 12 April Facebook comment that:

My empirical research shows a correlation between media frenzy and price, and between liquidity and price volatility, while my theoretical research concludes that the price will fluctuate more rapidly than with more liquid media of exchange (i.e. what we are accustomed to as money, or even highly liquid goods such as stocks or commodities). The fluctuations will continue until Bitcoin’s liquidity increases significantly.

Such approaches have essentially been warning that, “Bitcoin may well be in a bubble phase,” adding, “one of several large ones, just as we expected to occur along the way.” As a commentary on the price trend in late March and early April, this appears to have been a valuable assessment. These observers recognized in advance that the price seemed to be rising at a pace unlikely to be sustainable, driven perhaps by events in Cyprus and then a flood of popular media attention.

In sum, saying that “Bitcoin is a bubble” (total dismissal of the system as such) and that “Bitcoin is (or was) in a bubble phase,” are quite different claims. Now that another correction has arrived, this distinction can come into better focus.

The Bitcoin system is not the same as the peripheral trading services

The core of the Bitcoin system itself, which few people seem to grasp is something entirely different from the more visible currency exchanges and their price charts, seem to have been relatively untroubled. This includes nodes, mining pools, the blockchain, wallets, and even informal and P2P markets. Besides MtGox, with its 12-hour mini-holiday, from what I noticed, only some of the exchanges and data chart services were heavily challenged and went offline intermittently. Bitcoincharts, for example, reported a 25x spike in concurrent online users from 2,000 to 50,000, requiring “tweaking the backend” systems in response.

The primary proximate cause of the crash, then, seems to have been the inability of a (currently) key exchange service provider to keep up with demand fed by sudden media attention and buy-in frenzy in the run-up, triggering a classic emotional wave of panic selling, most likely the corollary of the previous heat of emotional buying. The existing trading infrastructure (which is not the same as the Bitcoin system infrastructure) was not ready to scale to such a rapid demand spike. This sharp correction might be viewed in part as the rather ungentle method by which the market realigned itself with the current real-world state of scaling capabilities and business planning skills at exchanges that have been working to build themselves from the ground up.

Creation versus destruction

In the case of a classical terminal hyperinflationary event, the authorities orchestrating it are better equipped and prepared. Ink and paper are ready. Printing presses run and are up to their tasks. More importantly, printing plate engravers are standing ready to carve additional integers, a relatively simple task of creating higher and higher denominations of notes. The technical infrastructure is in place for state money monopolists to completely destroy the value of a paper currency, using “zeroes” to drive it all the way to “zero” and extinction.

Building a new kind of media of exchange for a community of all-volunteer users from scratch through peaceful cooperation, entrepreneurship, coordination, debate, and market ecosystem building would appear considerably more challenging than destroying a paper currency. After all, being constructive often seems more challenging than being destructive; it requires greater ingenuity and long-term persistence and perspective.